NEWS

From Prison Cells to Presidential Palaces: Global Icons of Resilience

History has frequently demonstrated that the cold iron of a prison cell can serve as the ultimate crucible for transformational leadership. While incarceration is designed to break the spirit and silence dissent, for a select group of global figures, it became the very launchpad for their ascent to the highest offices of state. From the anti-apartheid struggles of South Africa to the velvet revolutions of Eastern Europe, the journey from prisoner to president is a recurring theme in the narrative of human freedom and political endurance.

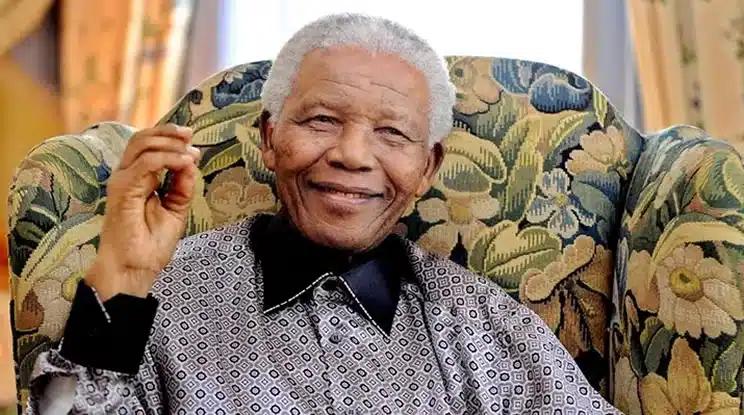

Perhaps the most universally recognized symbol of this journey is Nelson Mandela. For twenty-seven years, Mandela was the world’s most famous prisoner, held by South Africa’s apartheid regime for his role in sabotage and anti-government activism. His release in 1990 did not just signal the end of his personal ordeal; it marked the beginning of a new era for a nation. By 1994, the man who had been branded a terrorist was sworn in as South Africa’s first Black president, proving that reconciliation is often more powerful than retribution.

In South America, the story of José Mujica of Uruguay offers a different but equally compelling perspective. Before being dubbed the “world’s humblest president,” Mujica spent thirteen years in brutal conditions, much of it in solitary confinement, due to his guerrilla activities with the Tupamaros. Rather than emerging with bitterness, he transitioned into a leadership style defined by extreme austerity and progressive reforms, famously donating the majority of his presidential salary to charity.

The collapse of the Iron Curtain in Europe also brought forward leaders who had been forged in the fire of communist repression. Lech Wałęsa, a humble shipyard electrician in Poland, was detained in the early 1980s for leading the Solidarity movement. His defiance against the Soviet-backed regime eventually saw him move from a detention center to the presidency of Poland in 1990. Similarly, Václav Havel in Czechoslovakia spent years as a political prisoner for his human rights activism. A playwright by trade, Havel’s intellectual resistance culminated in the Velvet Revolution, leading him to become the first president of the Czech Republic.

Southeast Asia provides a modern example in the form of Malaysia’s Anwar Ibrahim. His political career was a roller coaster of high-level government service followed by decades of politically motivated imprisonment. Despite the legal battles and years spent behind bars, his resilience turned him into a reformist icon. His persistence finally bore fruit in 2022 when he was sworn in as Prime Minister, completing a decades-long quest for justice and democratic reform.

The African continent’s decolonization era was also defined by leaders who were familiar with colonial jail cells. Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe spent a decade imprisoned between 1964 and 1974 for his anti-colonial activism. While his later years in power remain a subject of intense controversy, his time in prison cemented his status as a revolutionary hero who led his country to independence. In Uganda, Yoweri Museveni faced incarceration in the 1970s for his opposition to the brutal Idi Amin regime. His subsequent guerrilla war eventually led to his long-standing presidency, which began in 1986.

In West Africa, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the father of modern Ivory Coast, experienced a brief stint in a colonial jail during his days of political organizing. That detention did little to stifle his influence; he went on to serve as the nation’s first post-independence president for over thirty years. His story highlights a common thread among these leaders: the belief that the struggle for national identity is worth the price of personal liberty.

The Americas also saw figures like Juan Perón in Argentina, whose brief imprisonment in 1945 actually worked to his advantage. The public outcry over his detention was so massive that it forced his release and catapulted him to the presidency in 1946, creating a political movement that still dictates Argentine policy today. In Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s roots in labor activism during the military dictatorship led to brief detentions in the 1980s. A former metalworker, his journey from the factory floor to the presidency in 2003 remains a beacon of hope for Brazil’s working class.

These ten leaders illustrate that the path to power is rarely a straight line. For them, the cell was not an end, but a classroom for strategy and a test of character. Their stories remind us that political legitimacy is often born from sacrifice, and that those who have known the weight of chains are often the most determined to break them for their people.